Bribery and corruption have long undermined the very processes countries require to build a stable and sustainable economic, political and social environment. In 2018, the United Nations estimated that the global cost of corruption amounts to an alarming $3.6 trillion. Of that cost, it is estimated that more than $1 trillion in bribes are paid each year.

The damages are myriad, but the good news is that countries recognize the harm that corruption and bribery cause, and they are working diligently to put an end them.

Bribery involves the offering and provision of money or items of value in return for favorable treatment—such as an expedited application process or advantageous contract bid outcome. On the opposite end, soliciting payment in exchange for influence is also considered bribery, and in some cases, receiving a bribe, whether it is solicited or not, is a crime. Although the U.S., Canada and Europe are generally considered countries with lower risk for bribery and corruption, bribery can flourish in all parts of the world. This proliferation is cause for concern, particularly as companies increasingly invest abroad and in offshore labor to cut costs.

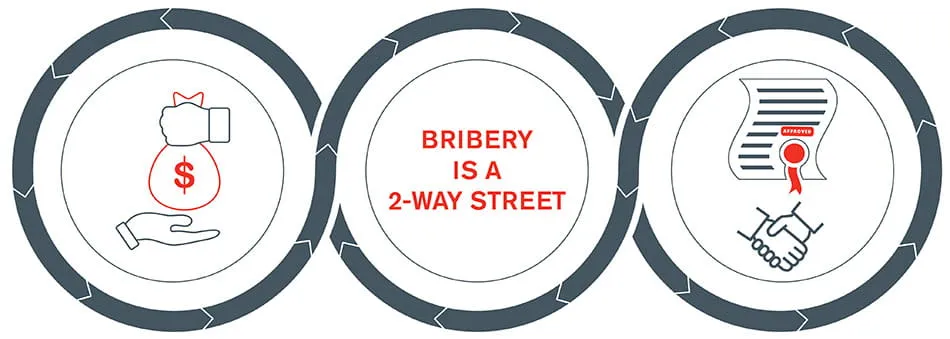

Bribery is an issue for many reasons. Among them, it increases wealth inequality, supports corrupt regimes and damages faith in democracy. Bribery impacts everyone by creating artificial price inflation, reducing public spending and encouraging monopolies. Without fair competition, corrupt actors can raise prices and control supply. Innovation is stifled because potential entrepreneurs do not trust the legal system to defend their intellectual property. Wealth then tends to be distributed in extremes of rich and poor, with a sparse middle class and little opportunity for small businesses to grow, creating a crippling cycle.

Arguably the largest blow dealt by corruption is the risks posed to public safety. Where corruption is rampant, shadow economies flourish, and businesses are disincentivized to play by rules that are not enforced. Corrupt entities put workers’ and consumers’ lives at risk by cutting corners and bribing their way out of health and safety regulations, often with disastrous consequences.

While the U.S. led the way with the creation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act over 50 years ago, the UK eventually enacted its own rigorous anti-bribery legislation—the 2010 Bribery Act—to combat graft in international business. As the ill effects of bribery are better understood, many other countries have followed suit and upgraded or redefined laws specifically targeting bribery and corruption over the last 10 years.

In the U.S., the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977, or the FCPA, upholds an anti-bribery provision making it illegal for individuals and corporations to pay or otherwise reward foreign government officials for their help in securing or retaining business. The FCPA also requires companies whose securities are listed in the U.S. to meet its accounting provisions, which include:

The FCPA’s anti-bribery provisions originally applied to U.S. citizens conducting business abroad but have since been extended to foreign companies and non-U.S. citizens who facilitate bribes inside the U.S. Foreign-owned companies conducting business in the U.S. must also adhere to specified accounting and record-keeping provisions. These provisions lend (sometimes vast) extraterritorial reach to the FCPA and its regulators.

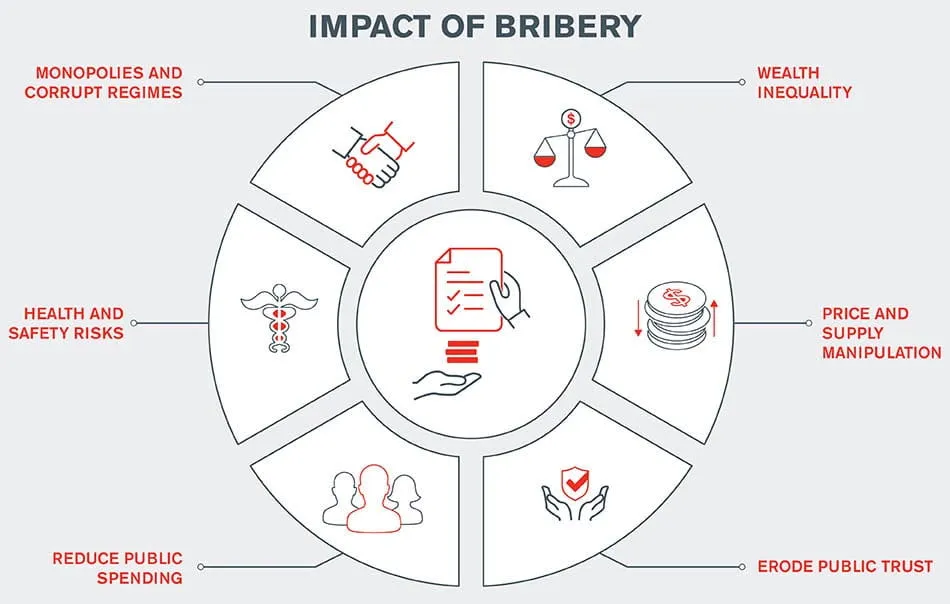

Through both criminal and civil action, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) in cooperation with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) enforce the FCPA, and potential fines vary:

Through a series of violations, the penalties for FCPA misconduct can accrue to much higher amounts than the separate violation thresholds. Historically, defendants often opt to settle charges without admitting guilt. This is done through a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA), usually in exchange for a settlement sum and agreement to certain terms and conditions.

In addition to fines, an FCPA violation can lead to disgorgement, a vehicle for preventing unjust enrichment allowing regulators to recover profits generated by an unlawful activity. FCPA disgorgements are based on the U.S. regulators’ view of the amount of profit generated by a corrupt transaction.

In the past dozen years, the top FCPA enforcement actions resulted in close to a billion-dollar penalty for one corporation, half consisting in fines, the other in a $457 million disgorgement. Other recent examples of FCPA enforcements include a company that violated accounting regulations when it paid for government officials to attend a sporting match. In another case, the officers of a U.S. company were fined for permitting the payment of bribes in a South Asian country. That company was also fined for anti-bribery and accounting violations. One other instance had a company’s vice president pay a $20,000 fine for evading his company’s internal accounting controls and violating the FCPA through improper payments.

In 2017, the DOJ revised the FCPA enforcement policy to emphasize enhanced corporate compliance programs, cooperation with the DOJ, voluntary self-disclosure and remediation. Furthermore, a DOJ ruling has been formalized that encourages interstate and international cooperation to prevent fines from being levied on one company by multiple jurisdictions.

Passed by the British Parliament in 2010, the Bribery Act criminalized bribery, the bribing of foreign government representatives and the failure by private companies to prevent corruption. It also made it an offense to be bribed. The act applies to UK citizens, residents and companies and organizations that are incorporated in the UK, or that conduct business in the UK—granting similar extraterritorial privileges as the FCPA. The Serious Fraud Office (SFO) enforces the act.

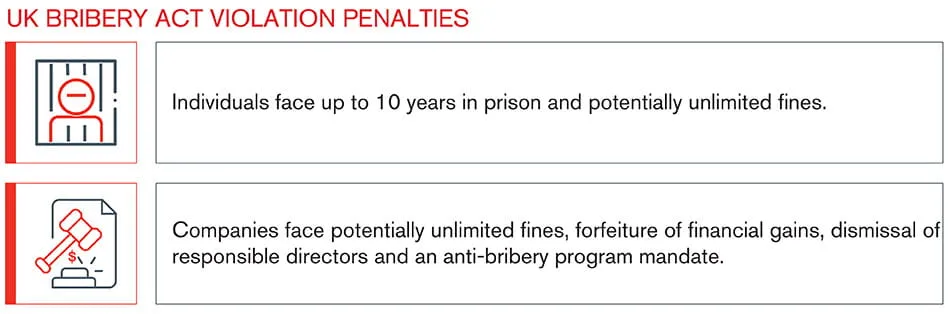

If found guilty of violating the UKBA, penalties per violation are more straightforward and stringent than the FCPA:

Violations can range from status quo bribery offenses to schemes to manipulate currency exchange rates (which in one case resulted in prison for some participants and the confiscation of more than 1 million pounds). In other cases, offenders, in addition to paying millions in confiscation orders, have paid tens of thousands in legal costs, and compensated their companies to the tune of hundreds of thousands of pounds.

The formation of the UKBA updated disjointed legacy laws against bribery and helped align UK law with the 1997 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Anti-Bribery Convention. Looking to the future, in July 2019, the UK government announced the launch of a comprehensive three-year plan to tackle economic crime, including strengthening its anti-money laundering controls through revisions to the Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) form submitted to law enforcement.

Both laws may take aim at the same problems, but there are still noteworthy differences between them:

| FCPA | UKBA | |

| Public or Private? | Prohibits bribing foreign officials | Prohibits bribing foreign officials and private business people |

| Intent? | Looks for intent | Doesn’t care about intent if the result was a bribe |

| Active or Passive? | Criminalizes only the paying of bribes and attempts to hide payments | Criminalizes both the paying and receiving of bribes |

The FCPA and UK Bribery Act are well-written and well-enforced. In 2018, corporations under FCPA jurisdiction paid a total of $2.89 billion in fines and profit forfeiture. Also in 2018, the UKBA’s SFO was believed to have around 70 active investigations, with 11 new criminal investigations opened. Meanwhile, FCPA actions totaled 38. So far for 2019, the SEC and DOJ have six current enforcement actions, with the largest fine totaling nearly $966 million.

2018 was notable for another reason. For the first time, the SFO successfully prosecuted a company for failure to prevent bribery. This action demonstrates that sound accounting and record-keeping practices, as well robust third-party anti-bribery and anti-corruption programs, are needed in order to satisfy the UK regulator’s requirement to have “adequate procedures” in place. Compliance programs, including internal risk assessments, ethical policies, due diligence questionnaires and automated screening and monitoring systems are increasingly being tested by the regulators. Kroll offers end-to-end anti-bribery and anti-money laundering solutions and training. Contact a consultant to get started.